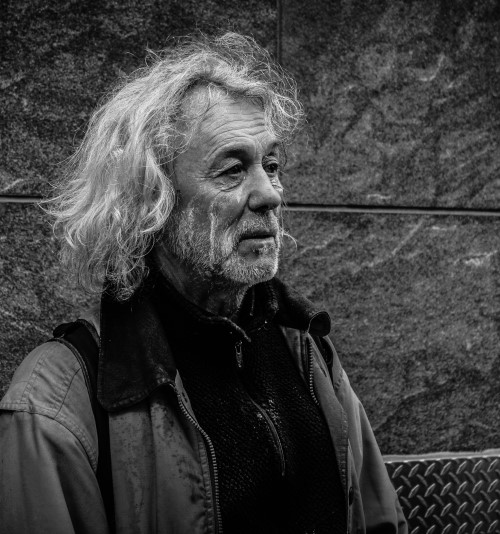

Homeless

All Australians deserve access to safe and secure housing. This is key to maintaining good health and feeling part of a community. People on low incomes are increasingly vulnerable to homelessness. There are over 100,000 homeless people in Australia according to 2016 ABS estimates. People who ‘sleep rough’ are the most visible to the public, yet represent a very small percentage of the homeless population. Many people experiencing or at risk of homelessness may live temporarily or couch surf with relatives or friends, in hotels, short-term and crisis accommodation, caravan parks and cars. People living in severely overcrowded accommodation, including boarding houses, may also be considered homeless. These individuals are known as the ‘hidden homeless’ population. People who are vulnerably housed (those who have frequent housing transitions, or insecure housing) may experience intermittent homelessness during their lives.

Anyone can become homeless, however, some Australians are more vulnerable to homelessness than others. Over half of the homeless population is male, but women experiencing homelessness, particularly women over 50, has risen significantly. People with disabilities are also more vulnerable to experiencing homelessness compared to the general population, and often have diverse housing needs.

There are negative public perceptions of homeless people, despite there being no ‘typical’ homeless person. Sometimes people who are managing well can experience homelessness after a stressful life event. A variety of factors can lead to homelessness, including:

- poverty

- changes to welfare and income support

- losing a job or unemployment

- financial difficulties

- shortage of affordable housing

- declining home ownership rates

- high rent

- housing crises

- losing a loved one

- relationship breakdown

- domestic and family violence

- earlier trauma, abuse or neglect

- drug or alcohol abuse

- physical and/or mental health issues

- gambling problems

- social exclusion

- leaving institutions such as the military, prison and state care

Refugees and asylum seekers are also at risk of homelessness. Homelessness has a high social and economic impact on society, but also a devastating cost to people and families in terms of self-worth, identity, health, relationships and work.

Homelessness negatively affects health due to a variety of risk factors. People experiencing homelessness are at a higher risk of many health problems, including:

- malnutrition

- mental health conditions

- substance use

- heart disease

- lung disease

- liver disease

- renal disease

- stroke

- diabetes

- cancer

People at risk of homelessness also face earlier ageing through the earlier onset of health problems typically associated with older age, including chronic health conditions, and other risks such as loneliness, social isolation, violence and trauma. Many older people experiencing homelessness do not have family or other social networks.

Homelessness and older adults

Adults aged 55 and over are considered ‘older’ in the context of homeless. The older homeless population has grown over the last decade. In 2016, one in six homeless people were aged 55 or over. Homelessness will continue to be an issue for older Australians, likely increasing in future due to an ageing population and declining rates of home ownership. This impacts aged care and palliative care support provision. Older adults experiencing homelessness usually live in boarding houses or temporarily stay in other households. Older women are increasingly at risk, especially single women over the age of 45 who are renting. Factors like domestic violence, relationship breakdown, financial difficulty and limited superannuation can put older women in particular at risk of homelessness.

Homelessness among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians make up a quarter of all people who are homeless, despite representing a minority of the Australian population. Accommodation difficulties and domestic or family violence are key reasons for homelessness among this group, which magnifies as remoteness increases. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people from remote areas may also find it difficult to adapt to living in urban environments, which increases their vulnerability to homelessness.

Access and service barriers for people experiencing homelessness

There are unique considerations in terms of service access and support when caring for people experiencing homelessness towards the end of life. People experiencing homelessness often have complex health needs, a lack of medical records and may have conditions with uncertain prognoses compared to others who are referred for end of life care. Many people experiencing homelessness have less interaction with healthcare professionals overall and many do not access primary care, meaning their health conditions are often not well-managed.

Physical and mental health issues can make planning treatment and care more challenging for people experiencing homelessness. To best support someone at the end of life, health professionals and care workers must be aware of the issues affecting people experiencing homelessness. An understanding of each persons’ unique life experiences, challenges, and needs is required. When working with older people experiencing homelessness, consider their living situation, social support network, psychosocial needs, contact with community services, history of substance use, and barriers to accessing care. Considering a person’s social history is an important component of assessing medical history.

People experiencing homelessness often have fears around how they will be treated and therefore may lack trust in healthcare professionals. They may have had negative experiences with healthcare settings in the past, and those who use drugs and alcohol may fear being judged or stigmatised by service providers and health professionals. There are also practical barriers to accessing healthcare for people experiencing homelessness, including often having to prove their personal identification and residential address before being able to access healthcare or medication. Homelessness often leads to difficulties finding work. People experiencing homelessness may also find it difficult to balance their competing practical, social and physical needs (including where to sleep and managing finances) with their often complex healthcare needs.

Where to get help

Homelessness Australia provides fact sheets on various population groups, and information on where to go for help if a person is experiencing homelessness in each Australian state and territory. Mission Australia also provides information about homelessness in Australia, organises housing programs, and provides a service directory search function. Mission Australia can be reached on 1800 269 672 or via email housingenquiries@missionaustralia.com.au. Housing for the Aged Action Group (HAAG) is an organisation specialising in the housing needs of older Australians, and National Shelter may also provide useful information on homelessness in Australia. The Salvation Army provide some housing and homelessness support. The DVA provide support specifically for homeless veterans.

Aged care considerations for people experiencing homelessness

Homelessness Australia have suggested that funding models of aged care specific to older people with experiences of housing insecurity and homelessness are required. Such models will look and operate differently from mainstream residential aged care facilities, as there are unique aged care considerations for people who are homeless or at risk of homelessness. My Aged Care have information for aged care providers about providing support for people facing homelessness and a government calculator for estimating fees for aged care services. People living on below $55.44 a day are considered financially disadvantaged or ‘low means’, and are eligible to have some or all of their accommodation costs subsidised by the government. Our ‘Financially and Socially Disadvantaged’ webpage provides information relating to aged care considerations that may also be useful for people experiencing, or at risk of experiencing homelessness.

Palliative care and advance care planning considerations for people experiencing homelessness

The Department of Health and Aged Care has released an exploratory analysis of barriers to palliative care and advance care planning report on people experiencing homelessness, which contains approaches for improving access and quality of care for this group. People with complex needs who are vulnerably housed may be at risk of dying without adequate care and support. Working with older people experiencing homelessness requires a multi-disciplinary approach. All staff should work closely with health, social care, and homelessness specific services when planning care and support towards the end of life, as other staff may help to identify changes in the person’s health. Developing links between general and end of life healthcare services and homelessness services can help to overcome barriers in care provision and can promote person-centred end of life care for people experiencing homelessness. There are unique considerations in terms of pain relief for people who have used drugs and alcohol. Specialist palliative care teams and substance misuse teams should partner to provide the best care possible, as people experiencing homelessness often have complicated pain relief needs and concerns. Those with addictions may experience withdrawal if their conditions are not properly managed. For people experiencing homelessness in the community, health often declines with little or no input from specialist health teams. When treating vulnerably housed individuals in shared accommodation in the community, there are often privacy issues and difficulties around finding a place for safe storage of medicines.

Health professionals and care workers may not have specific training required to provide best practice end of life care to people experiencing homelessness, and often find it difficult to know how and when to provide end of life support to these individuals. It is best to plan for end of life care for people experiencing homelessness as soon as possible, rather than waiting until you think they may be dying. Even if you can only make small steps to improving people’s experiences, simply being able to acknowledge and talk about vulnerability can be meaningful to a person.

Some people experiencing homelessness may not wish to move to other environments towards the end of life. Like most individuals, people experiencing homelessness want to die how and where they lived, which may include on the streets or in shelters. Staying in a hospital or hospice can be challenging for people with a history of homelessness. Medical environments may feel unfamiliar and uncomfortable, and people may display behaviour that is hard to manage. People experiencing homelessness may self-discharge before treatment or care is finished, which may mean hospital teams cannot properly communicate treatment plans and people may not receive appropriate ongoing care. Organising case reviews may help when caring for people whose care is complicated and may help to avoid crisis admissions to hospital. Ask each person you work with who they would like involved in their care, including outreach workers and others.

There are barriers to advance care planning with people who are homeless, which can further complicate end of life experiences. Some health professionals or care workers may fear communicating about difficult issues with people at the end of life, especially where they think people may be fragile due to past trauma. Remember, it can take a long time for people experiencing homelessness to develop trusting and nurturing relationships with services and health professionals. Health professionals and care workers must be flexible and non-judgemental in their interactions with people experiencing homelessness, and tailor care to each person. Using a person-centred approach to care means the person experiencing homelessness feels heard and listened to. This improves the experience of care and support they receive. Health professionals should work with and build strong and flexible relationships with local homelessness services and share their knowledge around end of life care and advance care planning with staff from these organisations. When working with people experiencing homelessness, initiate conversations about what it means to live well, and their future choices and preferences early. Some questions to start the conversation may include:

- Is there anyone you would like me to contact?

- Where do you want to be cared for?

- Is there anything that you would like to change?

- Are there substance use issues which we should discuss?

- What do we need to think about to plan for your future care?

- What are your fears or concerns towards the end of life?

- What do you want the end of your life to look like?

- How can we improve your end of life experience?

- What would a good death look like for you?

People experiencing homelessness may fear dying alone or anonymously, or worry about what will happen to their physical body after death, particularly where they feel distant from family, friends, and society. Marie Curie have developed a Homeless Palliative Care Toolkit, with practical tools and templates to support people experiencing homelessness at end of life. palliAGED provide resources which may be useful in planning and providing appropriate end-of-life care for people experiencing homelessness, particularly coordinating care between health and community service providers.